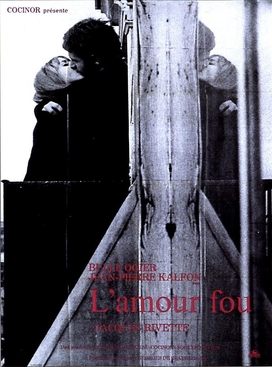

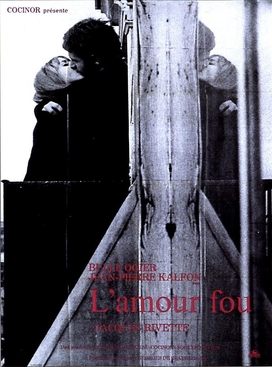

Jacques Rivette

1969

252 minutes

This film isn't as fun as the title (which roughly translates to "mad love") might suggest. It's a Rivette film, so you're getting a full four hours of movie. Stock up on crackerjacks, this is going into extra innings. It's a bit similar to his later film Out Hud, which has a nearly thirteen hour running time. In this one you're going to be watching a couple's relationship deteriorate, but both of them are in an experimental theater production of a play. This time the subject of the play-within-a-movie is Racine's Andromaque, based on the myth of Andromache and mostly taken from Euripides' play Andromache. Andromache was Hector's wife in the Trojan War.

The actual plot of the play is admittedly confusing as fuck and they do that weird alternate-history thing where through some trickery of the gods, character X wasn't really killed and an impostor was killed by mistake, which leads to a whole new and fresh plot twist for the characters involved. This is like Trojan War fanfiction, basically. You don't really need to know much of this for the plot to make sense, but you should at least have some sense of what they're rehearsing. And unlike the two theater companies in Out Hud they seem to have progressed here to the point where they have some sort of script and are using lines actually written by Racine. Oh, and plus there's a documentary crew filming the rehearsals for this because, as far as Rivette is concerned, give the people what they want. And there's a real market for watching endless hours of experimental theater luminaries deciding how they're going to interpret a centuries-old piece. Narrative-wise, this provides a frame and gives the film crew plenty of chances to interview characters firsthand about events taking place in the film so they can break the fourth wall and comment without actually breaking the fourth wall, somewhat like modern mockumentaries and sitcoms that have a mockumentary format.

The thought of Astyanax (the son of Andromache) not actually dying annoys you a bit when you read up on Wikipedia trying to figure out what the fuck is going on in the play they are rehearsing. In the version of the myth you are familiar with, Andromache's son Astyanax was thrown to his death from the walls of Troy as one of the cruel atrocities depicted after the fall of the city. This happens to form one of the funniest moments in one of your favorite pieces of postmodern literature.

Not long after you moved to Maryland, you read a book called The Sot-Weed Factor by John Barth, a postmodern novel that is the imaginary history of Ebenezer Cooke, a poet born in the seventeenth century who was an early migrant to Maryland. Cooke wrote an extremely satirical poem about his voyage to Maryland and the beastly people he met when he got there, entitled "The Sot-Weed Factor: Or, a Voyage to Maryland. A Satyr". Sot-weed is tobacco, and a sot-weed factor is basically a tobacco merchant. The novel is a fictionalization that fleshes out his story.

Within the story, Cooke is renowned as a notoriously bad poet. Early on he composes a pretentious heartfelt poem that starts with the following lines:

Not Priam for the ravag'd Town of Troy,

Andromache for her bouncing Baby Boy,

Ulysses for his chaste Penelope,

Bare the Love, dear Joan, I bear for Thee!

This poem is subected to withering criticism about sixty pages later for its poor choice of words and imagery, which is winkingly suggested to be clever wordplay:

"...Nor am I the dullest of readers: I quite appreciate the wordplays in your first quatrain, for instance.""Wordplays? What wordplays?"

"Why, chaste Penelope, for one," Sayer said: "What better pun for a wife plagued twenty years by suitors? 'Twas a clever choice!"

"Thank you," Ebenezer murmured.

"And Andromache's bouncing boy," Sayer went on, "that was pitched from the walls of Ilium--"

"Nay, 'tis grotesque!" Ebenezer protested. "I meant no such thing!"

"Not so grotesque. It hath the salt of Shakespeare."

"Do you think so?" Ebenezer reconsidered the phrase in his mind. "Haply it doth at that. Nonetheless you read more out than I put in."

"'Tis but to admit," Sayer said, "I read more out than you read out, which was my claim. Your poem means more to me."

Words to live by, these.

In any case, this is going to be a long ride.

Time to choose something different: